This post was last updated on July 13th, 2022 at 09:51 am

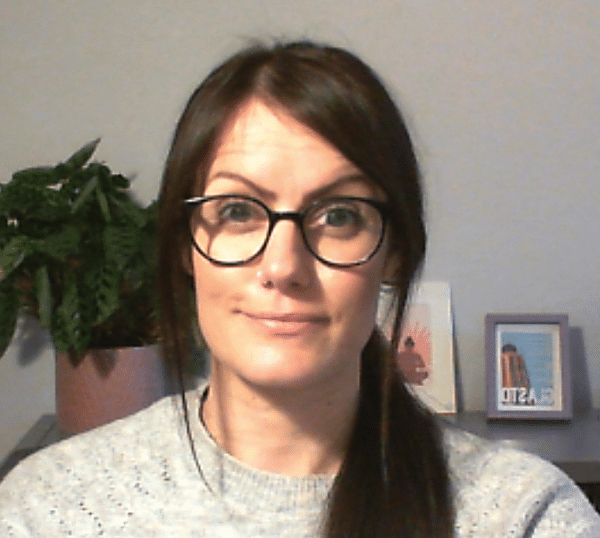

Long before COVID-19 arrived, health professionals were sounding alarms about the growing number of people leading sedentary lifestyles. It didn’t seem like the problem could get any worse, but it has. Measures taken to navigate the pandemic have also reduced physical activity levels, making the work of Dr. Abigail Morris and other sedentary behavior researchers more important than ever.

Morris, who is a lecturer at Lancaster University in the UK, has been focused on finding innovative ways to encourage people to move more. She recently conducted a study examining whether a smartphone app, called Stand Up!, would help office workers sit less.

For this study, office workers downloaded the Stand Up! app to their phones. Some workers received the app’s prompts and reminders to stand every 30 minutes and others every 60 minutes. Another group received no prompts at all. The results, she said, were promising. People who received the prompts and reminders to stand reduced their total sit time, while the 60-minute prompt proved most effective.

“What we found was that people who were in the group that got the hourly prompt were able to significantly reduce their sitting time” compared to the group that received no prompts, Morris said in an April interview with Frugalmatic.

Morris, who earned her PhD at Liverpool Moores University, became interested in studying movement interventions after working as a health and wellness officer in a low-income part of Northern England. In that position, she worked on community-based programs designed to help people eat healthier and become more physically active. Morris noticed a common connection among local residents struggling with health problems: sedentary lifestyles.

“Somewhat naively I was really focused on the physical activity side. I hadn’t really considered sedentary behavior. But once I saw how prevalent it was and the association with negative health outcomes, I couldn’t unsee that,” she said. “It’s steeped in every part of our daily lives. So I became very passionate about how to tackle that through innovative ways.”

The link between sedentary lifestyles and chronic conditions—such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and hypertension—is no secret. But many unanswered questions remain about how to keep people sitting less and moving more, especially over the long term.

“We’re interested in knowing more about the way in which we prompt and remind individuals to be physically active. The intervention I ran was very much a manual process (participants had to record in the phone app when they switched from sitting to standing),” she said. “How can we integrate the prompts so that they’re tailored to individual needs? Whether integrating it with someone’s work calendar or through a smartphone or wristwatch.”

Read more excerpts from the April 29 interview with Dr. Abigail Morris below:

Frugalmatic: What have you noticed about how the COVID-19 pandemic has affected people’s activity levels?

Dr. Abigail Morris: COVID has had a significant impact on our ability to be physically active. In the UK, our lockdown restrictions have meant that our typical avenues to be physically active—whether that’s the gym, sports field, playing park—have been shut down and restricted. And the amount of time in the UK that we could spend outside was limited.

It was good to see the message still come through that you had that time to go out once a day to be physically active. And I saw just anecdotally out my window people going past all day—so many people using bikes and running.

But a recent systematic review of 66 studies with over 86,000 participants showed a majority of people, pre- and post-COVID, had reduced the amount of time that they were physically active and had increased the amount of time they were sedentary.… Overall, there’s been a significant impact on physical health but psychological health as well. We’re only starting to see some of these things emerge.

F: For you personally, have you noticed a difference in terms of how it’s affected you in being physically active?

AM: Absolutely. I’m very mindful of it, as you can imagine. It’s steeped within my research. I don’t have a standing desk at my house. I moved, in March of last year (2020), to working from home, which has its benefits. But, actually, you don’t have any opportunities to commute. There’s not any kind of natural break for walking between meetings, getting a bit of fresh air. You go from team call to team call (by video conferencing)—back to back to back—and you don’t have those natural breaks in the day.

I also feel there’s this kind of assumption that you have to be sat down at a computer to be productive. But I learned throughout my PhD that sometimes being away, going for a walk and ruminating on some ideas, is when you have those light bulb moments. Just because we sat at a computer doesn’t mean we’re being productive 24/7.

Yeah, it’s kind of blurred the line between home work and life, the work-life balance. It’s just become very easy to just sit and work into the evening because there’s not much else to do, is there?

F: Fitness trackers and smartphone apps are seen as a possible solution for getting people to move more. On the other hand, it seems people’s use of digital technologies is what leads to a lot of sitting. In your opinion, which direction do you think technology will take society, more active or more sedentary?

AM: It’s undeniable what we’re seeing throughout the literature is this digital revolution has been responsible for a dramatic shift in the way we conduct our daily lives, in the way that we work, in the way we conduct our leisure activities.

But it’s not all been bad. Technology has allowed us to work more efficiently, more effectively, more productively in so many ways. Throughout the pandemic, it’s been absolutely valuable in allowing us to stay connected across the globe.

But this reliance on technology has also drastically increased our sedentary behavior and contributed to a significant reduction in our physical activity. Because essentially, we don’t need to move to be productive, to be members of society, to contribute to the economy. Typically, our workplaces—whether that’s at home or office environment—they’re set up to be predominantly seated, desk based. There are very few opportunities to be physically active throughout the day.

I do feel fitness trackers, e-health or mobile-health technology, offer us some potential to harness these behaviors in a way which can promote health. We have lots examples of tracking your sleep, tracking your menstrual cycles, tracking your food and alcohol intake, tracking your step counts….

What we’re seeing in relation to physical activity and behavior apps at the moment is quite a quick drop-off in user engagement between six to eight weeks. So you have this initial take-up and buzz, a novelty factor, around these gadgets. It’s encouraging. People seem to be quite motivated initially. That’s short-term impact.

But what we want to be able to do is have these things integrated into our daily lives and become quite habitual and unconscious behaviors. I think they do have their place, and they can allow us to become more aware. But also what we see within the literature is we need to integrate additional components, to allow people to understand why. It’s not just about being physically active, but what are the benefits of that? To try to get them to understand more the impact of these behaviors, not just in the short term but in the long term.

F: There’s a perception that the negative health effects from prolonged sitting can be “canceled out” by exercising. What have you learned about people who exercise a good amount but also spend a lot of time sitting and being inactive?

AM: There is some evidence that we’re able to offset some of the negative effects of sedentary behavior by becoming more physically active. However, we have to be very cautious how we interpret this data, or this message, in the interest of public health.

For individuals who spend upwards of eight hours sitting (per day), if they achieve 70 minutes of moderate to vigorous physical activity per day, there is some evidence that they are able to mitigate these negative effects of sedentary behavior. But the thinking is 70 minutes per day, and this is much higher than the minimum physical activity guidelines that we have at the moment (30 minutes of moderate to vigorous physical activity each day). A high proportion of our population don’t achieve the 30 minutes per day, and so it’s very unrealistic that people will be able to fit in 70 minutes per day.

4 books to inspire you to become more physically active

F: Is there an ideal balance that we should strive to have in terms of how much of our day should be spent being active versus inactive?

AM: There are 24-hour models that are being investigated at the moment. What we see is that our days are typically comprised of sleep (about 40% of the 24-hour cycle), light physical activity (about 15%), moderate to vigorous physical activity (about 5%), and sedentary behavior (about 40% to 50%). What we’re trying to do is encourage people to shift from the sedentary to the light physical activity throughout the day. There’s not specific guidance at the moment, but the World Health Organization thinks we should limit the amount of time we spent being sedentary and replace it with physical activity of any intensity, including light physical activity.

F: I’ve been reading some conflicting opinions about the benefits of standing desks. You can stand while being physically inactive, so does it make a difference to be standing at a desk versus sitting? Do you have any thoughts on that issue?

AM: A great question. While the comparative energy requirements between sedentary postures and standing are not entirely different, standing does consume double the amount of energy compared to sedentary postures. Standing also recruits different muscle groups which work to stabilize us while in a standing posture. The act of transitioning frequently between sedentary and standing postures is also of importance as it helps to mitigate the risks of prolonged time spent either sedentary or standing.…

The beauty of standing desks is that individuals who use them report feeling less fatigued throughout the working day, particularly after meal times (postprandial slump). And in the UK, call center workers reported feeling more alert and engaged when interacting with customers. The greatest benefits to health occur when an inactive individual engages in some physical activity. So I think it is still an important public health message to reduce sedentary time whenever possible.